There are over 2 million farmworkers in America.

In the United States, we enjoy abundant, affordable produce year-round. Yet, few realize where that food comes from and who grows it. Each year, around 2.5 million farmworkers and their families labor in fields and factories across the country to bring us fresh fruits, vegetables and other agricultural products that become our food.1

Although farmworkers provide invaluable and necessary goods and services, they often earn low wages and endure many job-related hazards, substandard working and living conditions including long hours, instability, and isolation. Farmworkers face substantial health challenges and experience many barriers to access care like language differences, high costs, and transportation barriers.3,4 Despite these challenges, farmworkers are incredibly resilient. They work hard, celebrate culture and family and strive to make a better life for themselves and their communities.

Who are Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers?

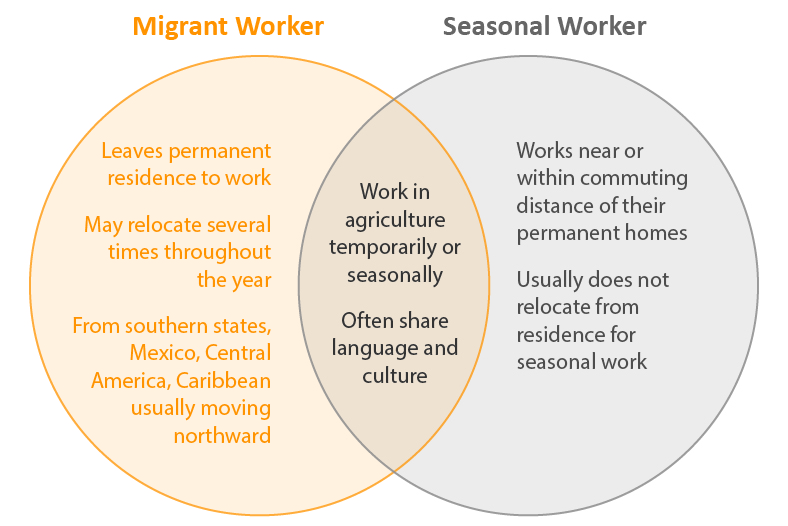

Migrant and seasonal farmworkers work in the same types of jobs and often share language and culture. Most find employment in the agricultural industry for less than half of the year and may supplement their income with earnings from other jobs. Although the term Migrant Seasonal Agricultural Workers (MSAW) is used to include migrant and seasonal farmworkers, there are some distinctions between the 2 groups.

A migrant farmworker is generally understood as someone who has traveled from their permanent residence to work in agriculture following the growing and harvesting seasons. Some may relocate several times throughout the year, whereas others spend months or an entire season at the same farm. A seasonal farmworker works in agriculture seasonally within commuting distance of their home and returns to their permanent residence each day after work.

Farmworker Demographics

According to the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) conducted in 2018 of approximately 2,500 workers nationally, approximately 77% of farmworkers identify as Hispanic, and about 61% are of Mexican descent.5 About 2 in 3 farmworkers surveyed are citizens or legal residents of the United States.5 In recent years, the number of immigrants employed in the agricultural workforce has drastically increased.5 Men, women, teenagers and children work in the agricultural industry. Sixty-nine percent of farmworkers are male, and a third are aged 35 years or younger.5,6

While some families migrate together as they have for generations, a growing number of young workers travel independently. Policy changes in immigration as well as in labor housing may be partly responsible for such trends.

77% of farmworkers

identify as Hispanic

–

69% of farmworkers are male

–

2 in 3 farmworkers are citizens

or legal residents of the United States

H-2A programs

Some farmworkers are part of a foreign labor force brought to the United States to work in the agricultural industry through guest-worker or H-2A programs, which permits U.S. agricultural employers to bring foreign temporary workers to the United States to perform seasonal agricultural work. However, the structure and implementation of H-2A programs can and often does create a working environment of poor wages and working conditions.

The Economics of Farmworkers

Over the last decade, farmworkers have faced even greater challenges earning a living. Poverty levels have remained high, and wages have failed to keep up with inflation.7 Many farmworkers earn annual wages below the federal poverty level. According to the recent NAWS survey, 21% of farmworkers live in poverty and the median income for farmworkers is between $20,000 and $24,999 annually.5 Moreover, farmworkers are not afforded the same federal wage protections as other American workers. The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) does not cover many laborers involved in certain kinds of agricultural work to minimum wage or overtime pay.8

Many labor laws and protection standards enacted through federal and state governments, which are designed to protect the health, safety and interests of workers have exemptions for agricultural employers. For example, the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which protects workers from retaliation for labor organizing, forming unions and collective bargaining, excludes agricultural workers.8 Furthermore, the worker protection standards that do apply to the agricultural industry are often not enforced. The result is working and housing environments that are potentially hazardous and can compromise the health, safety and well-being of farmworkers.

The Work and Crops of Farmworkers

Farmworkers contribute to the production and distribution of crops in almost every state in the U.S. performing many labors including:

- Plant, cultivate, harvest, process and package food for shipment and sale

- Stoop, work with the soil, climb, carry heavy loads and directly handle plants and pesticides

- Harvest crops like apples, asparagus, beans, blueberries, cherries, chilies, cucumber, eggplant, grapes, melons, mushrooms, onions, oranges, peas, peaches, peanuts, peppers, pumpkins, raspberries, squash, strawberries, sugar beets, tobacco and tomatoes

Farmworker Health

Farm labor results in unique challenges to the health of farmworkers and their families. Farmworkers may face poor dental health, diabetes, hypertension and mental health issues.11 Agriculture is one of the most accident-prone industries in the United States, and workers in the industry face the highest fatality rate in the nation.12 Occupational challenges faced by farmworkers include pesticide exposure, infectious diseases, respiratory issues, hearing and vision problems and musculoskeletal conditions.13 Poor living conditions such as overcrowded or poorly maintained housing and lack of clean drinking water can have negative health impacts.

Many farmworkers do not have access to regular, affordable health care, often lacking coverage through their employers or public programs, and they do not earn enough money to pay for health insurance. Only 56% of farmworkers report having health insurance.5 Over half of the farmworkers surveyed in the National Agricultural Workers Survey cited cost as the major difficulty to accessing health care.5 In addition, farmworkers typically cannot afford to take time off from work or to risk losing their jobs to seek medical care. Transportation challenges, language and cultural differences and limited clinic hours also create barriers. Follow-up and continuity of care present additional challenges as many farmworkers relocate several times each year and do not maintain permanent addresses or phone numbers.

Female Farmworkers

Female farmworkers face the additional risks of sexual harassment and sexual violence. While the national prevalence of sexual harassment and/or violence experienced by farmworkers is unknown, some studies suggest up to 80% of farmworkers may be experiencing this issue. Often, the problem of sexual harassment is left unaddressed due to fear of deportation or job loss, embarrassment or shame, and barriers like language and available resources.14,15

Child and Adolescent Farmworkers

Child and adolescent farmworkers are especially at risk for adverse health effects and consequences of agricultural work. Many children working as farmworkers suffer more frequent respiratory, parasitic, and skin infections, diarrhea, nutritional deficiencies and oral health issues.2 Children who are still developing are particularly vulnerable to these hazards.2

Education of Farmworker Children

Migration and agricultural work often interrupt formal schooling. Moving regularly can make it difficult for farmworker children to complete their education. The median highest grade of schooling obtained by foreign farmworkers is at the eighth-grade level.5 Children and young adults often work to contribute to the family income. They may miss part of the school year, attend multiple schools each year, face discrimination or have little time for their studies or any extracurricular activities. Educators estimate that only 45% to 60% of children in migrant households nationwide graduate from high school.9

In addition, students from farmworker families may struggle with language differences or be met with low expectations from educators. Through funding from the U.S. Department of Education, Migrant Education and Head Start programs through local school districts provide children of migrating families with supplemental education and development programs designed to help close the educational gap. Despite the added challenges of interrupted education and migrant life, farmworker children have plans and aspirations that include pursuing higher education.

Strengths of the Farmworker

Farmworkers are extremely resilient. They endure and often overcome the difficulties of hard labor, poverty, discrimination, interrupted schooling, health problems, and fragmented health care. Dedication to family and community provides a strong support system for farmworkers. They take pride in who they are and their indispensable role in providing food for the nation, and work hard to provide a bright future for themselves and their families.

Many farmworkers work with local, regional and national organizations to improve conditions and health for all farmworkers and their families. Farmworkers have helped develop and sustain successful Community Health Worker (CHW) programs, or Promotor(a) programs, in their camps and communities. A Community Health Worker is a trusted member of the community who empowers their peers through education and connections to health and social resources.

CHWs in these programs build on community strengths; farmworkers teach each other and address the unmet health needs of their friends and neighbors through education, referrals, peer support, advocacy and networking with service providers. This is at the heart of MHP Salud’s mission, as migrant farmworkers were some of the first communities to adopt Promotor(a) programs created by MHP Salud. Learn more about our history here.

Only 56% of farmworkers

report having health insurance

Educators estimate that only

45% to 60% of children in migrant households nationwide

graduate from high school

How We Can Help You

CHWs can effectively communicate and connect with farmworkers’ cultural norms due to shared culture, language, and identity. CHWs are equipped to provide community-based, health-related services, such as assistance with translation, case management, and advocacy.

MHP Salud offers free resources to promote the physical and mental health of farmworkers and to support the CHWs who work in these farmworker communities. Click below to learn more about how we can assist in starting or maintaining a CHW program!